Prisons are expensive. Are they actually working?

/This article was first published in The Westsider Newspaper

By Jennifer Piper

Prisons are expensive. In the 2014-15 financial year, Australia spent $2.9 billion on them. We’re also sending more people to prison than ever before. Especially women. Over the last ten years, Australia has seen a 77% increase in the total number of women in prison.

About a third of the people currently in prison are on remand. That means they have been charged, but not found guilty or sentenced. They’re just stuck in prison while they wait for a court appearance.

‘This all begs the question, What are prisons for? If we’re sending more people to prison are the prisons actually helping anyone, outside or inside?’

Image by Nico Photography

Victoria is particularly good at overcrowding and over-sentencing. More people are on remand than ever before, and more people are being refused parole (and so kept in prison for their full sentence). You might think this is because crime is on the rise, but statistics say otherwise.

There’s a whole bunch of research that suggests neoliberal countries (think Australia and USA) tend to lock up more of their population, while social democracies (think Scandanavian countries) do not. There are also some very clear links between social welfare and rates of imprisonment. Countries with good social welfare services don’t tend to lock up as many of their citizens as other countries. So, as the gap between Australia’s poorest and richest people widens, so will our rates of incarceration.

But are the prisons effective?

Nope.

Increasing sentences doesn’t encourage people to stop criminal behaviour. In fact, criminalising someone (by unnecessarily imprisoning them) tends to increase their likelihood to reoffend.

Locking more people up, “...does not reduce the rate of serious crime, discourage potential offenders or reduce re-offending rates.” [Mirko Bagaric, Dean and Head of School of Law, Deakin University]. When a person is released from prison and tries to return to their community (as most do), they are often left with less options for housing and employment and so more reason to view criminal activity as the only viable option.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the majority of women in prison are there for nonviolent crime. Most prevalent are drug offenses and “offences against justice procedures, government security and operations.” Of the women in prison, about a third grew up in foster care and two-thirds have been in violent relationships. More than a quarter of these women have tried to kill themselves. When women do commit violent crime, it is most often in response to being the victim of violent crime.

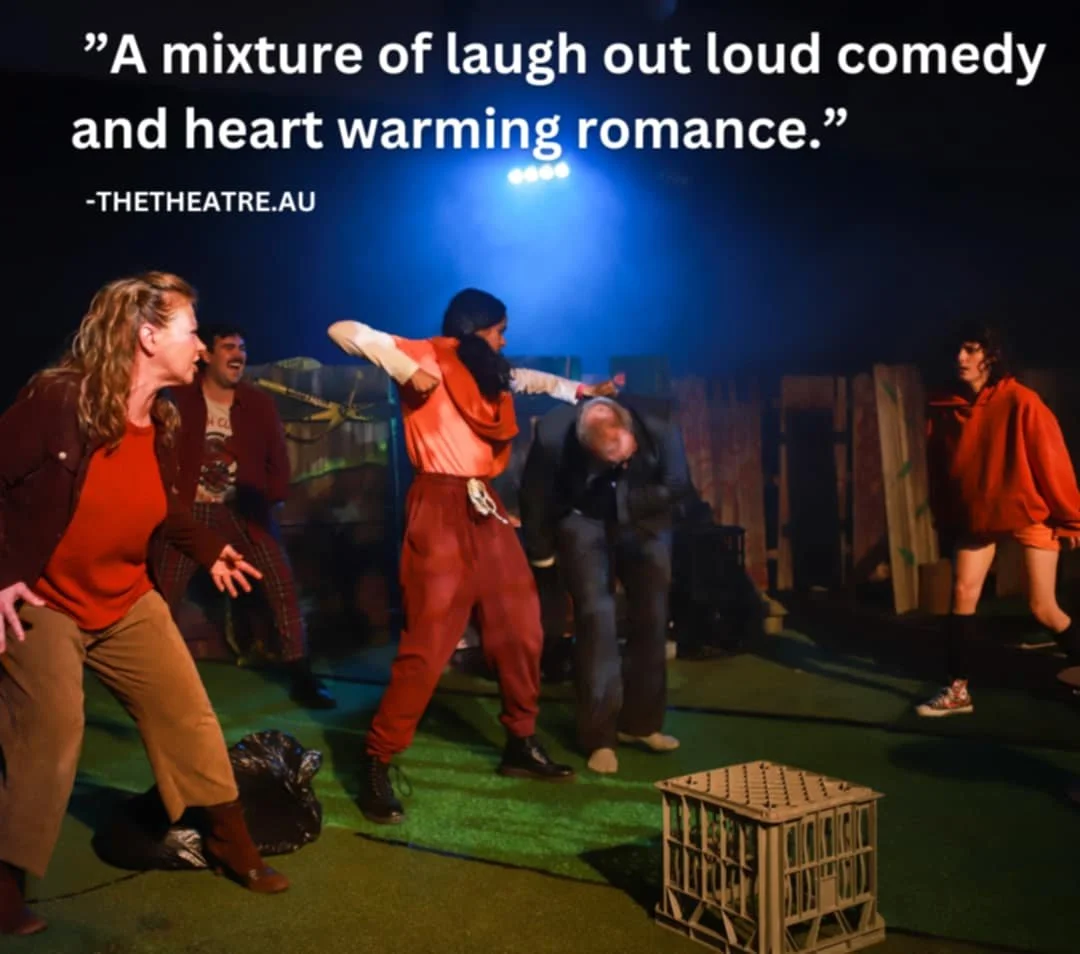

In Hilary Beaton’s Outside In (currently being performed by wit incorporated at Bluestone Church Arts Space), we see seven women subjected to life in prison. Almost all of them are there as a result of chance or circumstance. Only one is a credible danger to people outside of prison. These women do not benefit from being locked up. Their imprisonment keeps nobody safe. The punitive nature of life in prison – constantly grasping to maintain privileges and play the game to end up on top – dehumanises and brutalises them.

They, like all the rest of us, just want to feel loved and safe.

Just because we were founded as a colony of convicts, doesn’t mean we should be aiming to replicate that situation today. We’d save a lot of money and, more importantly, a lot of lives.

Outside In is at Bluestone Church Arts Space until Saturday 4 November.